Scapulothoracic Joint…NOT the shoulder?

- Mar 15, 2023

- 8 min read

My last blog explored medical definitions of ‘the shoulder’.

While anatomical descriptions identify the scapulothoracic (ST) joint as part of the ‘shoulder', most standardized shoulder assessment guidelines exclude this region. If mentioned at all, the ST joint is identified as an ‘extrinsic’ cause of shoulder pain.

This blog will explore what sets this joint apart from the rest of the ‘shoulder’. Why do most ‘shoulder’ experts omit or exclude this one articulation within the shoulder joint complex?

There are many exculpatory reasons for this. The following synopsis provides four of them.

The scapulothoracic joint is not a ‘real’ joint.

The first reason that might help to explain why the ST joint is not considered part of the ‘shoulder’ is an anatomical one. The ST ‘joint’ is not technically a joint. Most of the joints in our body have a specific architecture. A typical synovial joint is characterized by shiny articular cartilage that coats the ends of the bones. A fibrous sac or covering encloses the ends of the bones (joint capsule) and within the sac, there is a small amount of liquid (synovial fluid). The synovial joint is designed for movement. The shape of the bony ends, and the number and direction of ligaments within (fibrous disc) and around the joint, will determine which movements will or will not occur. The glenohumeral joint is an example of a synovial joint. It has a “ball and socket” shape that allows motion in three planes and around three axes.

The ST ‘joint’ also allows and limits movement, but the mechanism is entirely different.

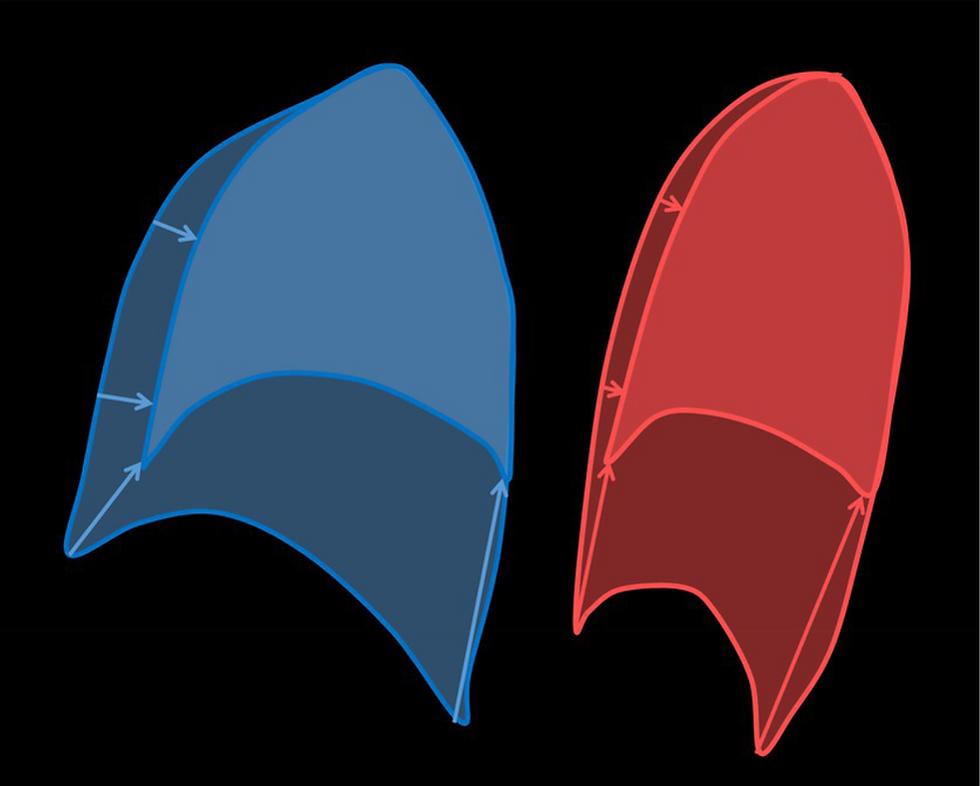

The ST joint is a “sliding junction” between the concave, muscle-lined surface of the scapula and the convex, muscle-covered surface of the rib cage between rib levels # 2 and #7. This unique articulation relies entirely on muscles for support and positioning on the chest wall. (Frank R. et al.)

Seventeen muscles attach to and enshroud almost every surface of the scapula. Nine connect the scapula to the humerus or upper arm bone. These are called scapulohumeral muscles. The remainder connect from the scapula to the axial skeleton. The scapula-to-axial skeleton muscle group (A and B) are called the scapulothoracic muscles. Large muscles from the torso, pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi, can also change scapular position indirectly. When they pull down on the arm, the arm will bring the scapula down with it (dark line at the bottom of the diagram).

Medical Orthopedic specialists who have claimed ‘the shoulder’ as their specialty, have focused their efforts on the bone, joint and muscle (scapulohumeral) problems that occur primarily at the glenohumeral joint because imaging (Xray, Ultrasound, MRI) can almost always confirm a diagnosis, surgery is often appropriate, and outcomes are, for the most part, predictable.

The NON-joint between the scapula and the thorax relies on the interactions of many labyrinthine layers of muscle, bone, nerves, and bursae*. Boney pathology involving the scapula itself can generally be identified on X-ray, but the scapular muscles have a network of widespread attachments. For the ST joint to operate normally, 17 muscles of variable size, shape, and direction, need to act in concert with each other.

*Bursae – A small, fluid-filled sac that reduces friction between layers of tissue.

A problem in this region can possibly trigger symptoms that are felt in the shoulder and upper arm, the head, the neck, or the back.

Shoulder ‘specialists’ are not prepared to examine a complex problem that may involve the ribs, the spine, or multiple layers of muscle that occupy the neck and most of the upper back. While the SCAPULA itself is easily recognized as part of the shoulder complex, its indecipherable network of attachments is NOT.

Scapular dyskinesis – altered scapular position or movement. Scapular dyskinesis is the first, and often the ONLY indication that there is a problem at the ST joint.

Sometimes the scapula sits a little higher or lower than it should or tilts a little one way or the other. It may wiggle a little bit as the arm is raised – sometimes the dyskinesis is very slight and most of the time these small variations of ‘normal’ are overlooked because they happen frequently, and most of the time, the small movement anomalies at the scapula are the result of an injury or problem at the GH joint.

This kind of dyskinesis is referred to as secondary dyskinesis.

Primary dyskinesis can look the same as secondary dyskinesis, but the reason for the altered movement or position of the scapula is different. Primary dyskinesis occurs when there is a problem affecting the ribs underneath the scapula, the scapula, the ST bursae, or the ST muscles.

This is the second reason why shoulder experts often overlook the SC joint…

Unless there is a severe deformity or winging at the scapula, the assumption is made that dyskinesis is secondary.

The rationale is: Manage the GH problem and an appropriate exercise program should look after the scapular dyskinesis.

Clinical signs that may indicate a primary ST problem, are interpreted as GH-related, and the focus of the examination remains GH.

This is an excerpt from the introductory statement in a 2021 paper, Scapulothoracic Dyskinesis: A Concept Review

“Scapulothoracic dyskinesis (SD) occurs when there is a noticeable disruption in typical position and motion of the scapula which can result in atypical and inefficient motions of the arm and shoulder [3, 4]. SD typically occurs secondary to numerous separate pathologies of the shoulder including injury of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint, rotator cuff tear, clavicular fracture, shoulder impingement, multidirectional instability, and labral injury…”

This brings us to the third reason…

Primary dyskinesis, due to a scapulothoracic problem, is rare.

A review of the medical literature will confirm that this statement, based on the number of recognized cases, is true…

The most common cause of primary dyskinesis (often referred to by the term: winging scapula) is a condition called long thoracic nerve palsy (LTNP). It is also sometimes called serratus anterior palsy. Fardin et al. reported an incidence of 15 cases out of 7,000 patients seen in an electromyographical laboratory.

Overpeck and Ghormley reported only one case out of 38,500 patients observed at the Mayo Clinic.

The second most common cause of primary dyskinesis is spinal accessory nerve palsy (SANP).

It is also sometimes called trapezius palsy.

According to Orth et al,

there are as many as 23 different etiologies* that can cause primary dyskinesis (winging scapula). Osteochondroma (bone cancer) is one example. ALL are rare.

*Etiology – Describes the cause or causes of a disease or an abnormal condition.

HOWEVER

Medical literature is not infallible. In fact, medical literature and medical research are rife with false claims and bias, especially when…

“...the studies conducted in a field are smaller; when effect sizes are smaller; when there is a greater number and less preselection of tested relationships; where there is greater flexibility in designs, definitions, outcomes and analytical modes…many current scientific fields claimed research findings may often be simply accurate measures of the prevailing bias” (Loannidus, JPA, 2005)

If a condition is considered RARE, is it truly rare or rarely diagnosed?

Both patients shown here, have long thoracic nerve palsy. Both have primary dyskinesis.

The patient on the left has left scapular dyskinesis with no observable winging. The patient below has marked winging – yet, both patients have the same diagnosis.

Marked winging is rare. Dyskinesis is not.

How does a ‘winging scapula’ define primary scapular dyskinesis?

The short answer is that it does not. The appearance of 'winging' depends on local muscle length and tissue flexibility. This will vary, depending on age, sex, posture, state of health, body type and chronicity. Affected muscles that do not recover will lengthen over time.

For some, primary scapular dyskinesis will present with very subtle changes in scapular position or movement. For others, the displacement is hard to miss.

Recent studies of 3D shoulder complex kinematics

are showing us that there are measurable and consistent differences in scapular position and movement between those with shoulder complaints and those without.

Subtle primary dyskinesis is complex, often difficult to see and poorly understood.

Our fourth and final reason is a simple one:

No one is looking.

“Scapular” specialists are almost non-existent – there are only “shoulder” (glenohumeral) specialists.

“To perform an examination of muscles, bones and joints, use the classic techniques of inspection, palpation and manipulation. Start by dividing the musculoskeletal system into functional parts”

Medical professionals learn how to assess the spine, the shoulder, the hip, the elbow and the ankle. Each piece of the body is presented as a separate part of the whole, with the understanding that these pieces do not function as independent units.

The exponential growth of scientific, medical, and biomechanical knowledge has made specialization a necessity for most healthcare professionals. As medical science becomes more complex and technologically advanced, the specialties have become progressively more splintered. To keep up with current technology and research, specialists need to narrow the scope of their specialty. As a result, patients can benefit from the most advanced and specialized treatment models for their condition.

Unfortunately, this specialization model only works when a patient fits certain criteria. Specialists have become adept at dividing the musculoskeletal system into functional parts. However, this narrow focus can often result in losing sight of the… understanding that these pieces do not function as independent units.

“You see what you expect to see, Severus.”

― J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

Medical practitioners can only make decisions based on what they are able to see.

What we see is coloured or altered by what we have been taught, our accumulated knowledge and our past experiences.

This phenomenon is called motivated perception. Psychological research confirms that this bias exists in all of us. The world as we conceive it is not exactly an accurate representation. Our perception and judgement can be biased, selective and malleable, and these influences can literally alter how we see the world. Psychology Today July 2019

Medical education bias tells practitioners that a ‘shoulder’ problem is rarely the result of a scapular or ST problem. Therefore, the position and movement of the scapula are either not observed at all or observed superficially, screening only for obvious or disfiguring anomalies.

If there ARE patients suffering from undiagnosed, unresolved ST joint problems, they have most likely become chronic. Those who are suffering but able to get on with their lives, just disappear. The medical profession did not provide a solution, so they stopped looking for one. For those who need to continue attending medical clinics, to return to work or sport, for example, these patients may have been identified at some point, as having one of these “diagnoses”:

Chronic Pain = unexplained muscle, joint and or nerve pain (neck, back, shoulder, head or arm).

Myofascial Pain Syndrome = unexplained muscle pain (neck, back, shoulder, head or arm).

Parsonage-Turner Syndrome = unexplained nerve involvement/palsy (neck, back, shoulder and arm).

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome = unexplained upper extremity weakness and, for some, …fatigue and shortness of breath with minor exertion.

These widespread symptoms do not 'appear' to be 'shoulder'-related... Some patients with primary scapulothoracic problems do not report any ‘shoulder’ symptoms, only complaints of pain in and around the shoulder blade and neck.

So. Is the scapulothoracic ‘joint’ part of the ‘shoulder’ or is it not?

The answer will depend on your perspective.

Do you see only the singular ‘shoulder” joint, the GH joint and its muscles,

or are you comfortable recognizing that our ‘shoulders’ can carry the “weight of the world”?

My goal is to provide objective and unbiased information; however, I do recognize that motivated perception affects us all. Here is mine: I am a former physiotherapist, I am older, female and I have a longstanding disability due to a scapulothoracic injury.

A different point of view can offer a refreshing change from the bias that has prevailed in the medical profession until very recently. (Fillingim 2009)

Changing perspective is a choice. Be ready for more interesting facts and discussions…coming soon.

Comments