Understanding Sexual Dimorphism and Its Impact on the Female Shoulder

- Janet Delorme

- Dec 26, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Dec 27, 2025

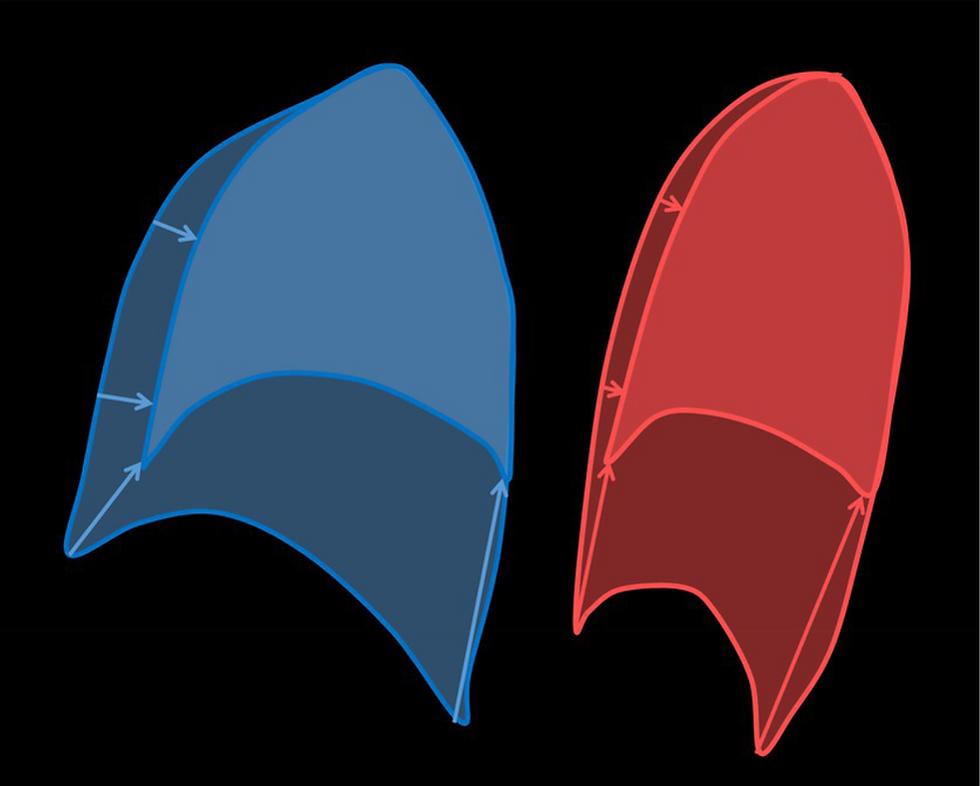

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366013055/figure/fig7/AS:11431281238423782@1713905624903/Illustration-of-a-sagittal-lung-cross-section-at-the-beginning-large-area-and-at-the.tif Illustration of male (blue) and female (red) lungs. Research.net

What is human sexual dimorphism?

Sexual dimorphism refers to the biological and physical differences between males and females, especially as they relate to disease manifestation and treatment. This field, also known as gender-based medicine, examines how diseases can present differently in each sex. Traditionally, medical research has focused predominantly on men, resulting in a uniform approach to treating both male and female patients. However, recent studies have shown that symptoms and responses to treatment can vary significantly between sexes, prompting a greater emphasis on sex-specific research.

Our current understanding of the human body is largely based on medical knowledge accumulated over generations. Historically, research has almost exclusively involved male participants from specific age groups. This focus has resulted in an incomplete picture, potentially overlooking important differences among various populations. Recognizing and understanding sexual dimorphism is crucial, as it acknowledges that physiological differences between men and women are not merely due to differences in size or scale, but are inherently sex-related and significant.

Why study sexual dimorphism of the shoulder?

The shoulder remains one of the most complex and poorly understood regions of the body. Its definition, classification, and associated epidemiological data reveal that chronic shoulder pain continues to be a major societal and financial burden. Notably, studies consistently identify women—especially those aged 45 to 64—as the group most affected by ongoing shoulder symptoms.

How do size, shape and proportion differ when comparing male and female upper body anthropometrics?

An AI search on "Sexual dimorphism and the human shoulder" provides an excellent summary of how male and female scapulae exhibit sexual dimorphism. Recognizing these differences is important because a disparity in scapular size and shape does have an impact on shoulder performance. However, it is not just the scapula that contributes to sexual dimorphism of the shoulder. The scapula has a symbiotic relationship with the axial skeleton, specifically with the thorax, and this relationship is essential for normal functionality of the shoulder. Investigating one-half of the arm/thorax connection is not only myopic, but it also serves to reinforce a cognitive bias that currently prevails in our understanding of the human shoulder.

Significant sexual dimorphism also exists in the thorax. A comparison of male and female size, shape and proportion of both the scapula and the thorax will provide a broader understanding of chronic and unexplained shoulder symptoms.

The following table highlights and compares thoracic (including lung) and scapular anthropometric data for males (M) and females (F):

Lung size | F 10-12% smaller |

Rib cage/spine dimensions | F rib cage smaller, M wider and broader, esp. caudally. F shorter diaphragm length. M thoracic vertebrae larger with more dorsally oriented TVP's/ribs, resulting in ribs with increased med-lat diameter T5-9. |

Rib inclination | F greater rib inclination, disproportionate growth of the rib cage relative to lung, and more ventrally oriented processes as well as rib curvature. |

Thorax/lungs shape | Sternum position is higher in F. M lungs are larger, shorter, wider caudally and pyramidal in shape. F lungs smaller, narrower, stay the same shape - more prismatic. |

Scapula | Scap size increases relative to body height. M tend to have larger scapulae than F for the same body height. Mean M scap is sup/inf taller and med/lat narrower than F. Glenoid is larger, more retroverted and less superiorly inclined, acromion and supraspinatus fossa are A/P broader in M. F glenoid is more oval-shaped. During arm elevation, scapular upward rotation angle is significantly less than that of M, internal rotation angle is significantly greater in F. Consistent with patients with MDI*(Ogston and Ludewig) |

Upper body muscle mass | M up to 75% more upper body muscle mass than F |

References - Bellamere 2003, Torres-Tomayo 2018, Bastir 2014, Garcias-Martinez 2016, Chapman 2017, Hamzehtofigh 2023, Lee 2024,

Discussion

Lungs:

Torres-Tomayo 2018) propose that the differences in lung shape between males and females will reflect a greater contribution of the diaphragm in males during breathing (Romei et al. 2010), which expands the lower lungs mediolaterally, as well as greater intercostal muscle action in females (Bellamere 2003). Torres-Tomayo also suggest that the greater contribution of intercostal muscles in females may be an adaptation to the gestation period ( Bellamere 2003, LoMauro & Aliverti, 2015), as pregnancy leads to hormonal and anatomical effects on the respiratory system (Contreras et al. 1991; García‐Río et al. 1996; LoMauro & Aliverti, 2015). This could explain different patterns of muscle recruitment between males and females, and the resulting variation in lung shapes.

Transverse processes and the ribs:

Bastir 2014 , found more dorsally oriented transverse processes in males at T1 and T5–T9, and more superiorly oriented facets for the articulation of the rib tubercles in females, indicating a different position of the ribs at the costotransverse articulation. In males, the orientation of the transverse processes leads to a reorientation of the ribs, which increases the medio-lateral diameter of the rib cage at lower levels (T5–T9). This, along with the more ventrally oriented processes in females at these levels, as well as the greater rib curvature Chapman 2017, could lead to these sex‐related shape differences.

Because females have greater rib inclination, Bellemare et al. (2003) suggested a different pattern of respiratory muscle recruitment between males and females, with females showing a greater contribution of the intercostal muscles. Males show predominant diaphragmatic action due to their greater mediolateral expansion. Lung shape differences between sexes suggest that females have a predominant ‘pump‐handle’ rib movement, while males show a predominance of ‘bucket‐handle’ movement of the ribs. Torres-Tomayo 2018

Scapulae:

Lee 2024 states that researchers have proposed the role of sexual selection in human evolution on fighting performance in male-male competition, leading to male-biased upper body specialization (Morris, Cunningham, et al., 2019).

The approximately 75% greater upper body muscle mass in human males corresponds to greater upper body strength, as well as male-associated scapular shape characteristics, such as the superio-inferiorly broader blade shape, which increases the breadth of the attachment sites for rotator cuff muscles and periscapular muscles. Bigger muscles, bigger attachment sites. This could also explain why male scapulae are larger than female scapulae for the same body height.

These sex differences in scapular shape may have biomechanical implications. Lee 2024 provides a summary of examples and studies where specific scapular features are considered at risk, resulting in altered shoulder joint mechanics, muscle moment arms (Lee et al. 2020), and glenohumeral joint reaction forces (Viehofer et al 2015).

Many characteristics of the female scapula are consistent with injury-associated shape differences: (Lee 2024)

Higher critical shoulder angle(Moor et al., 2013): narrower SS fossa, laterally projected acromion, superiorly inclined glenoid),

Superior/inferior shorter and medial/lateral broader, resulting in narrower attachment sites for rotator cuff muscles, and likely alters lines of action and potential for stabilizing the humeral head.

Superiorly inclined glenoid - theorized to predispose humeral head to superior migration, increasing load on SS (Hughes et al., 2003)

Anteverted glenoid - may increase stress on posterior rotator cuff (Tetreault et al., 2004)

While sexual dimorphism of the human scapula can be measured, scapular size and shape are highly variable across all humans, and the variation explained by sex is very small.

Future three-dimensional research is needed for a better understanding of the scapula's highly variable structure.

Scapulothoracic relationship

By combining these sexual dimorphic features for both the scapula and the thorax, we can take a more informed approach when observing them when they are working together.

Females have:

Mean scapular shape that is wider and shorter, with narrower (a/p) acromion and supraspinatus fossa.

Significantly smaller, less pronounced shoulder muscle mass.

Smaller, more prismatic-shaped lungs. Greater rib curvature and greater rib inclination

Breathing kinematics that favour increased use of accessory muscles.

Males have:

A larger scapula than females of the same body height

Mean scapula shape that is taller and narrower, with broader, thicker muscle attachment sites.

Approximately 75% greater upper body muscle mass compared with females.

Larger, broader, pyramidal-shaped lungs. Ribs are flatter, more horizontal, with increased med/lat diameter

Breathing kinematics favour increased use of the diaphragm.

Once again, I have inserted information that is specific to the serratus anterior (SA) muscle and the long thoracic nerve (LTN). While there are other important scapulothoracic neuromuscular structures to consider, my in-depth understanding of the SA muscle and the long thorac nerve provides me with the best examples where both the thorax and the scapula are essential players.

Consider this photo of the exposed lateral/exterior surface of the ribs with the SA muscle visible (Lt. - LTN, U - Upper fibres of SA, I - intermediate fibres SA, L - Lower fibres of SA). There is a distinct impression on the surface of the ribs (mostly under label "I", where the scapula had been recently lifted - as shown in the adjacent drawing.

To make this marked impression on the chest wall, scapulae would need to be shaped reciprocally to accommodate the shape of the underlying ribs.

Females have more rib curvature than males, who have wider, flatter ribs. It is logical to assume, therefore, that female scapulae are slightly more curved than those of males.

A male or female, with normal muscle mass and normal muscle tone, will present "normally" when observed from behind.

However, if this normal muscle mass that occupies the subscapular space is lost - muscle wasting due to palsy, for example, the observable 'gap' will be, or will appear to be, much larger in males for the following reasons:

75% more upper body muscle mass. Bigger gap.

A longer, narrower scapula with larger posterior scapular musculature is more visually prominent than a comparatively smaller, wider scapula with significantly smaller muscle volume.

Lifting of the medial scapular border is more easily seen when the reciprocally shaped surfaces of scapulae and thorax are flatter and less curved

Loss of muscle tone in the shorter, more oblique female SA fascicles will create laxity within the myofascial connections to the scapula.

Fig 6.3 - illustration of myofascial continuity of the spiral line. A mechanical connection through the spinous processes to the rhomboids, to the scapula, and then to the serratus anterior. (Myers T. Anatomy Trains 2001)

Scapular control and stability require a well-balanced length/tension relationship. These two drawings are from Thomas Myers' book, Anatomy Trains. Muscles that draw the scapula superior/medial; rhomboids, as an example shown here, work in concert with the SA, which can draw the scapula inferior/lateral.

Fig 6.4 - Taken together, the rhomboids and serratus anterior form a myofascial sling for the scapula Instead of a snug, balanced connection, the scapula now slides more easily in the direction where the remaining support lies...superior/medial.

Without this balanced support, stabilizing the scapula in multiple directions, the scapula will be more susceptible to the force of gravity. A force that will be exacerbated by the weight of the unsupported arm, as well as activities like lifting and carrying.

SA fascicles, attaching to male ribs, which are longer, flatter, and more horizontal, will also be longer and more horizontally projected than the SA fascicles. In males, the loss of muscle tone of denervated fascicles will likely translate to increased laxity at the medial scapular border—a bigger gap. Myofascial connections at the scapula are equally important, but the more horizontal rib orientation creates a more horizontal, less gravity-susceptible platform or 'sling' for scapular support.

With greater rib inclination and a higher sternum in females, loss of SA will create increased demand for compensatory/antigravity mm use. (levator scapula, upper trapezius, rhomboids). A compensated scapula will move to an elevated position on the chest wall. The elevated scapula will use pectoalis minor to assist with medial rotation and anterior tilt as it follows the smaller contours of the upper chest wall. From this elevated, compensated position (the 'up and over position), the medial scapular border will appear to rest normally, with no gap.

Summary

The male and female images used to illustrate male and female Scapulothoracic relationship, above, clearly demonstrate the contrasting elements described in the text.

However, significant individual variation in the size and shape of the scapula, the thorax, as well as the upper body muscle mass is the norm. Our genetics, race, state of health, age, and lifestyle are all factors that affect the size, shape and therefore the outward appearance of our scapula and thorax, and ultimately how the scapula appears on the chest wall.

When a single variable, such as sexual dimorphism, contributes to this complex dynamic, observational differences, as shown above, are rarely as easily determined.

A patient, male or female, with a more subtle presentation of scapular winging can easily be misdiagnosed.

Sometimes, no winging is observed. When the subject is at rest, AND when the subject attempts a wall push-up (The 'up and over' scapular position is very stable).

Sexual dimorphism may explain why males with long thoracic nerve palsy are often easier to identify. Significant individual variation AND sexual dimorphism, together, make simple observation an inconsistent tool for diagnosis.

Beyond observation...

What clinical signs or symptoms might help identify a "shoulder" problem that is secondary to a primary thoracic pathology? (LTNP used as example here)

Overall weakness of the arm, especially when lifting overhead. No rotator cuff pathology.

We already understand 'weakness', but do not measure it in the clinic because this weakness stems from the thorax, and we do not have a reliable, recognized test that would clearly identify the muscle or muscles of origin.*

*A clinical test, described in my book one, Scapulothoracic Assessment in Three Simple Steps, can isolate serratus anterior - especially useful with strength ranges 0-3. However, the practitioner must understand how the scapula moves three-dimensionally on the thorax and have hands-on clinical skills to assess scapular position and movement.

We need a recognized 'gold standard' method of determining in vivo scapulothoracic movement. Until this becomes a reality, clinical testing is the only tool in the toolbox.

The YouTube video, from near the end of blog 7 (YouTube, blog 7), clearly demonstrates differences in rib stability and movement when the LTNP side is compared with the normal side.

The power of the kinetic chain is engaged as the ribs elevate during arm elevation. When the arm elevates independently, without this intimate connection to the thorax, it will be significantly weaker.

Non-specific arm weakness, especially overhead, will result when the arm is expected to work on its own. The arm CAN move overhead, but it feels heavier and tires easily because the real powerhouse it relies on is no longer on board. Continued attempts to use the arm will result in fatigue, and persistent use after the arm is tired leads to tissue inflammation due to poor compensatory mechanics.

Complaints of fatigue and/or shortness of breath - despite normal X-rays and no history of respiratory illness.

Women, with greater reliance on their intercostal muscles and their compensatory antigravity scapulothoacic muscles, are more likely to experience fatigue and shortness of breath due to loss of serratus anterior function.

The use of the intercostals and the diaphragm is sufficient for resting and sedentary activity. However, the accessory breathing muscles, especially the serratus anterior, provide the necessary rib elevation and stability during activity, especially work or sport that requires strong, overhead, or repetitive arm movement. Men of the same body height have a larger diaphragm and a more horizontal rib orientation, so the loss of accessory muscle use will have a smaller impact on their breathing effort.

Fatigue is a difficult symptom to measure because it is subjective in nature.

A subtle increase in respiratory effort, combined with an undetectable but nearly constant use of compensatory antigravity scapulothoracic muscles, will increase overall energy cost. Like a slow leak, this nearly imperceptible, ongoing drain on reserves will result in symptoms. Individual variables apply, but fatigue and pain are real.

Put our new perspective into the clinical frame...

A healthy, older, active woman reports arm weakness, shortness of breath and fatigue. Reported shoulder/arm pain is variable*. Diagnostic testing for rotator cuff pathology is negative...

*LTNP + a sedentary lifestyle = may report no pain. LTNP + an active work/sports lifestyle and/or overachiever, AA personality...will likely work through pain until failure...

Let's put this valuable research to the test and start changing how we look and listen.

Comments